The Roots of the Coronavirus and Environmental Crisis

The coronavirus emerged because an an-human ecosystem was penetrated by humans and rejigged for exploitation. Maybe it was just two guys with a pickup truck – with the same mind that drills for oil in the arctic and mines at the bottom of the ocean. Like climate change, mass extinction, and habitat loss, the cross-species transmission of pathogens is caused by relentless exploitation of the living and mineral world. All these crises are one crisis.

Beyond Technical Solutions: Addressing the Worldview

We can respond to aspects of this compound crisis with technical solutions. But we should also try to address the root cause, a certain understanding of the world as existing for our taking. All of the earth’s surface–land ice and water–is now seemingly divided into areas for production, extraction, mobilization, disposal, reserve, consumption, recreation, and spectacle. Even in the most distant forest, the standing-reserve that Heidegger warned us about hums louder than a refrigerator. Nature and wilderness have lost their meaning. Every park, landscape, or vista that matches our expectation of it–whether spectacular, useful, or banal–is closed to us, nothing more than a cipher to us.

Spiritual traditions and practices could lead us to an intuition of the world as sacred. But we architects, designers, planners, and artists are on the secular side of the human project, committed to a worldly awakening.

Rediscovering the An-Human World

We who live in industrialized society have almost completely lost the ability to see the world in its otherness: an-human, unfathomable, existing, shifting, fecund, myriad. More than anything, we need a glimpse of that world. It won’t happen on the screen. It can’t happen if we are desperate about survival. Spiritual traditions and practices could lead us to an intuition of the world as sacred. But we architects, designers, planners, and artists are on the secular side of the human project, committed to a worldly awakening. How can we help those who almost understand, to understand? And those who do understand, to understand more deeply? The most appropriate place to cultivate a regard for the world, to expose the world as precious in itself (sacred), is paradoxically the city.

The City as a Portal to the Sacred

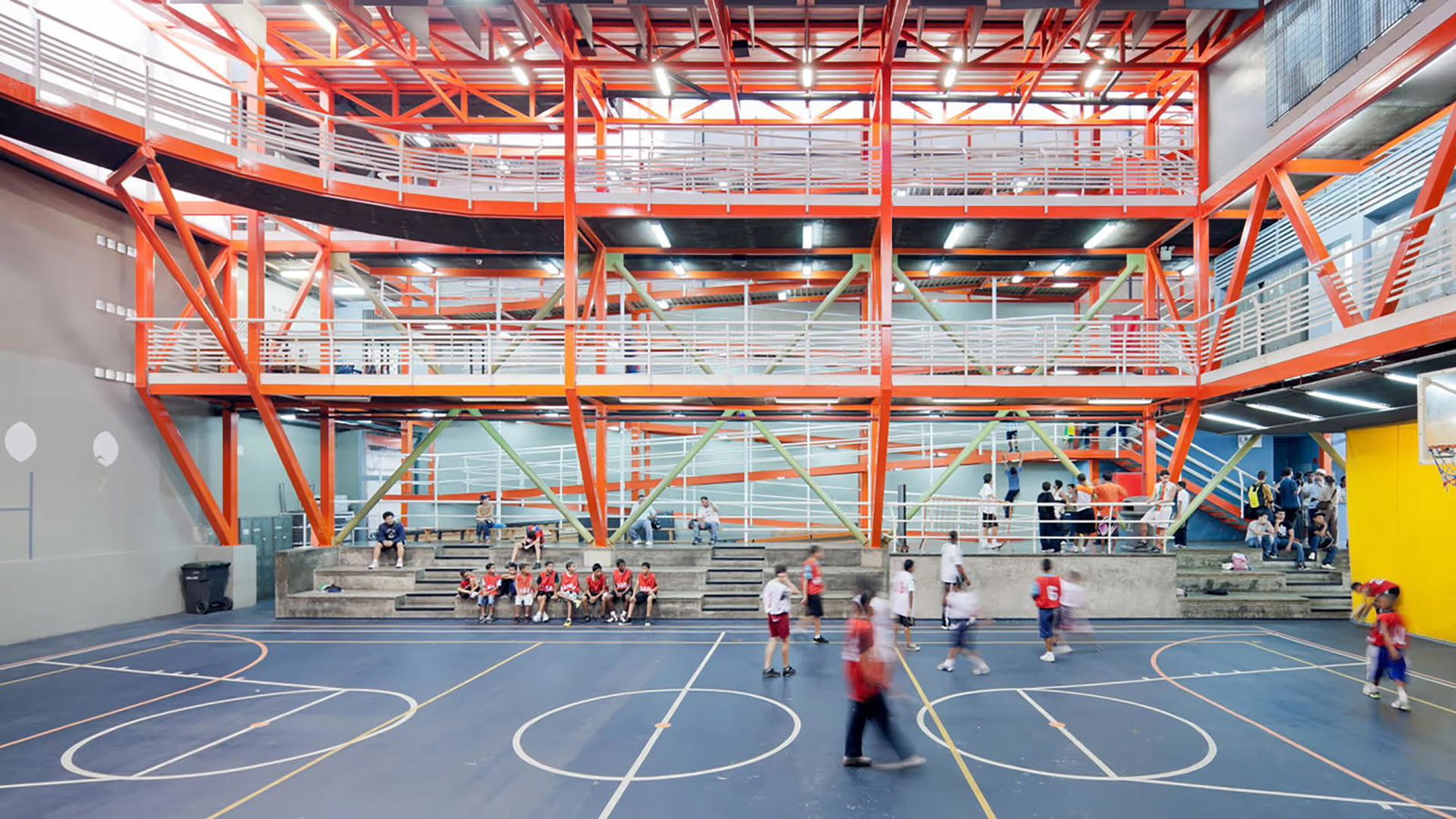

Rural areas are ecologically less diverse than cities, and depopulated areas must remain off-limits. In any case, we need to focus on the city because we need as many witnesses as possible. Urban designers/planners, landscape architects, botanists/ecologists, and artists can work together to re-frame meeting places between human and non-human. We need places to encounter non-human rhythms and life forms; to reflect upon the complexity and otherness of the living world; to discover strange beauty. Interrupting everyday routines in mid-stride, in the middle of the city. Ecologically, these places could function as biodiversity preserves and habitat corridors. Landscape architect Gilles Clément [http://www.gillesclement.com/art-469-tit-The-Garden-in-Motion] is a pioneer. The peace that is emerging here and there because of the global economic shutdown–less noise, traffic, pollution, production, and consumption; more sound of wind and birds, more reflection, more time–gives us a glimpse of the world on the other side of the crisis.

.avif)

.avif)